For the past ten years, rising watch prices from brands like Rolex and Patek Phillipe have become one of the most reliable flashpoints in modern collecting culture. Flaring up every time a brand updates a price list or a boutique quietly refreshes its website, usually followed by screenshots of old catalogues and a familiar sense that something has finally gone too far. But has it?

Strip away the emotion, and the picture becomes more nuanced, because while prices have undeniably risen, the scale of those increases looks very different once watches are viewed alongside inflation, property, precious metals, the aftermarket, and even alternative assets like crypto, all of which quietly shape how value is perceived, whether brands like it or not.

The difficulty with any long-term comparison is that watch brands rarely stand still. References evolve, movements are upgraded, case sizes creep up, bracelets improve, and collections are deliberately repositioned higher, often framed as refinement rather than reinvention.

The most honest way to track the last decade is to follow flagship models that have remained conceptually consistent. Think Rolex Submariner, Omega Speedmaster Moonwatch, TAG Heuer Carrera. Not perfect comparisons, but close enough to reveal the direction of travel.

Take the Rolex Submariner, the watch most often cited as the epicentre of price outrage. In the mid-2010s, a steel Submariner Date typically sat in the high US$7,000–8,000 range depending on the market.

Today, the current Submariner Date lists for around US$14,000 (AUD $18,500). That places the increase somewhere around 25 to 35 per cent over roughly a decade. Significant, yes, but far removed from the doubling that memory and social media discourse often suggest. Much of the frustration surrounding the Submariner has less to do with list price and more to do with access, waitlists, and the way scarcity has reshaped the buying experience.

The Omega Speedmaster tells a slightly different story. A Speedmaster Professional Moonwatch with Hesalite crystal could be purchased in the mid-2010s for roughly US$5,300–5,500. Today, that same core watch costs around US$7,000–8,000 (around AUD $12,000).

Curated news for men,

delivered to your inbox.

Join the DMARGE newsletter — Be the first to receive the latest news and exclusive stories on style, travel, luxury, cars, and watches. Straight to your inbox.

That represents an increase of roughly 45 to 50 per cent, meaning the Speedmaster has comfortably outpaced inflation over the same period. Omega would argue, with some true justification, that this reflects a genuine technical upgrade, including Master Chronometer certification and a new calibre, rather than pure margin expansion.

Worth noting, Omega’s Dark Side Of The Moon Speedmaster went from $14,000 AUD at the time of first release to $24,000 in around 10 years. That’s a more considerable watch, but its availability makes it a much more attractive option for many buyers. No fuss, just get it on your wrist.

TAG Heuer’s Carrera occupies a more accessible tier of the Swiss luxury market, yet follows a similar trajectory. Around 2015 or 2016, a steel Carrera chronograph typically listed around US$3,500–4,500 (roughly AUD $5,200–6,700).

Modern Carrera chronographs with the Heuer 02 movement now cost US$5,500–7,000 (around AUD $10,500 for a CBS2210.BA0048), placing the increase roughly in the 30-50 per cent range. Again, noticeable, but broadly in line with the wider industry rather than wildly ahead of it.

Across large-volume luxury brands such as Rolex, Omega, TAG Heuer, Cartier, Breitling and Longines, comparable flagship models have generally been up by between 25 and 55 per cent over the past decade.

Move further upmarket, and the increases become more aggressive, with Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin and Richard Mille often landing in the 50 to 90 per cent range depending on reference, material and how deliberately the brand has leaned into exclusivity. These brand don’t mess around and rightly so.

That sounds confronting until the lens widens. Inflation across most developed economies over the same period has ranged from roughly 25 to 35 per cent. Watches have outpaced the cost of living, but not by an absurd margin. They have become more expensive in real terms, but not wildly detached from broader economic reality.

Property, by contrast, has surged far harder. In cities like Sydney, Melbourne, London and New York, median house prices have climbed anywhere from 70 per cent to well over 100 per cent over the same timeframe, making watches look almost restrained by comparison.

Gold provides another useful reference point.

Over the past decade, it has risen roughly 60 to 70 per cent, while platinum has broadly tracked inflation with periods of volatility. Many watch prices, particularly steel sports models and precious metal references, have effectively moved in line with gold, which is notable given that watches are finished goods layered with brand equity, marketing and distribution costs rather than raw commodities.

Any serious discussion about watch pricing over the past ten years is incomplete without addressing the grey market and aftermarket, even though brands will insist it does not influence official retail pricing. In reality, the aftermarket acts as a powerful psychological signal. When a steel sports watch trades at double retail for years on end, it reshapes expectations.

Brands see sustained demand at higher price points, retailers see customers willing to pay premiums elsewhere, and buyers recalibrate what feels normal. Retail prices do not rise because of the aftermarket, but they are unquestionably emboldened by it.

The Rolex Submariner illustrates this perfectly. While retail prices have risen roughly 25 to 35 per cent over a decade, aftermarket prices at their peak surged far beyond that during the pandemic-era frenzy, with professional steel models trading north of US$18,000–20,000.

Even as the market cools, those years left a lasting imprint. Paying retail no longer feels expensive when the alternative has already trained buyers to accept far higher numbers. The same applies to watches like the Royal Oak, Nautilus and Daytona, where the gap between retail and secondary pricing became so wide that retail itself started to feel artificially low.

Once the conversation shifts from emotion to value retention, watches inevitably get compared to other luxury goods, and that comparison is revealing because it clarifies what watches are, and what they are not.

Handbags sit at the top of the luxury return hierarchy.

Hermès Birkin and Kelly bags have delivered extraordinary performance over the past decade, in some cases outperforming equities, gold and property, driven by extreme supply control, relentless demand and near-universal brand recognition. Chanel has followed with aggressive pricing of its own, turning certain classic bags into asset-adjacent objects almost by accident.

Fine wine occupies a more complex middle ground. Blue-chip producers and regions have delivered strong long-term returns, but the market is opaque, storage-dependent and sensitive to global cycles. Wine rewards patience and infrastructure, making it an investment first and a pleasure second, which fundamentally changes how most people engage with it.

Watches sit somewhere between these worlds. A small number of references have delivered exceptional returns, largely driven by scarcity and aftermarket demand, while the majority track inflation modestly or outperform it by a reasonable margin.

As a category, watches are not the strongest-performing luxury asset, but they are among the most liquid, culturally visible and emotionally engaging. They are worn, used, talked about and passed on, delivering daily utility in a way that wine in storage or handbags in safes do not.

And then there is the comparison that makes all of this slightly uncomfortable. Crypto.

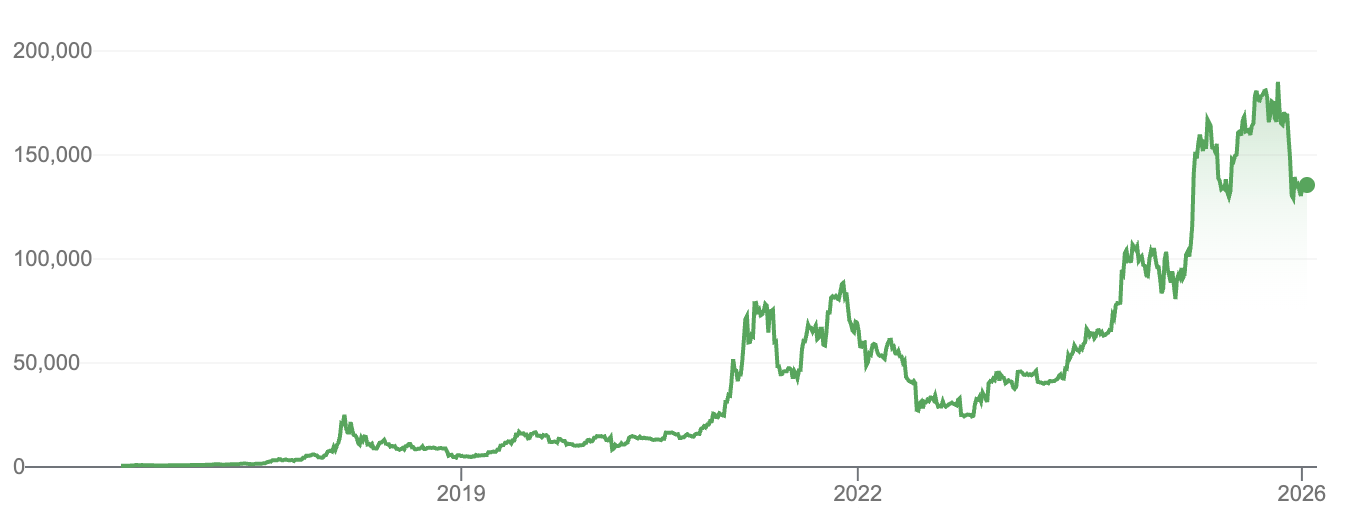

In 2016, Bitcoin was trading roughly between US$500 and US$700 (around AUD $750–1,050), volatile, poorly understood and widely dismissed. At the same time, a steel Rolex Submariner sat comfortably around US$7,500–8,000 (AUD $11,000–12,000), while an Omega Speedmaster could be bought for closer to US$5,000 (around AUD $7,500).

Fast forward to today, and the contrast is stark. A US$10,000 investment could have grown to over US$2,000,000 at today’s valuations. That’s like comparing an apple and a buy, but the 20,793% return is pretty sweet.

Against that backdrop, a Submariner rising 25 to 35 per cent or a Speedmaster climbing 45 to 50 per cent is almost irrelevant. Bitcoin is a high-volatility, high-risk speculative asset that rewards early conviction, timing and an iron stomach. Not I.

Seen through this wider lens, the frustration around watch prices begins to shift. Over the past decade, watches have risen broadly in line with inflation, tracked precious metals, underperformed property, lagged handbags at the extreme end, and been completely dwarfed by speculative assets like crypto.

What’s happening for most is our pay packets are not moving in the same direction, thanks to a fairly woeful global economic outlook. Throwin a few wars and some pandemics and we’re got ourselves a bit of a poop sandwich.

So, should we stop complaining? Probably.

Scrutiny keeps brands honest and prevents excess from becoming normalised. But perspective is overdue. Watch prices have risen, sometimes sharply, but when viewed against inflation, property, precious metals, the aftermarket, and alternative assets have largely moved in step with the world around them.

The real shift has not been the price itself, but access, scarcity and the widening gap between retail fantasy and retail reality. And that change, more than any percentage increase on a price tag, is what has fundamentally altered how buying a watch now feels.