- The modern luxury watch strap has evolved from a functional accessory to a modular tool.

- Brands like Cartier, Vacheron Constantin, and IWC are investing in proprietary quick-change systems.

- Amid economic pressure, strap swapping has emerged as a cost-effective way to refresh a $20,000 watch without buying another.

Before luxury timepieces became collector’s items, before Instagram wrist rolls and opulent fairs in the heart of Swiss watchmaking, watches were tools, fit for purpose. And the strap, if it existed at all, was a means to an end; something to keep the piece from slipping off the wrist.

But in the evolving world of horology, the strap has undergone its own revolution. For many, it’s no longer an afterthought, but a defining feature of an exquisite timepiece; one that can redefine a reference, elevate its profile to suit the occasion, and transform a single dial into a full week of wears.

From Pocket to Wrist: A Wartime Pivot

In the 19th century, men carried time in their pockets, hidden from view and often attached by chains to the inside of the jacket. They were functional, formal and familiar, serving only to tell the time at a quick glance.

Curated news for men,

delivered to your inbox.

Join the DMARGE newsletter — Be the first to receive the latest news and exclusive stories on style, travel, luxury, cars, and watches. Straight to your inbox.

The wristwatch only gained legitimacy when soldiers needed to synchronise manoeuvres without fumbling through a waistcoat. British officers began soldering lugs onto small pocket watches and attaching them to leather straps. These were unsophisticated and, at time, crude solutions to an everpresent problem on the frontline. But they worked.

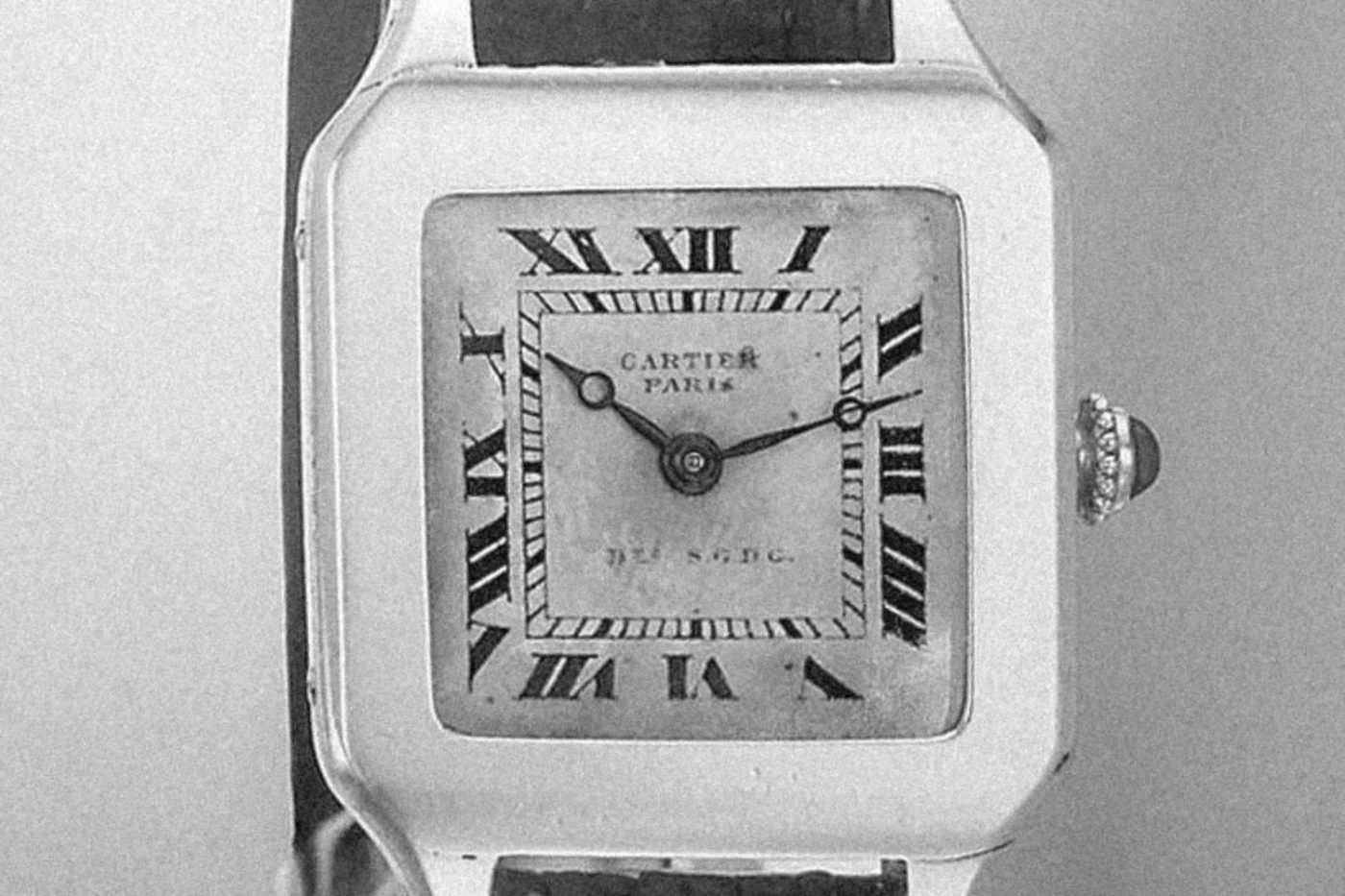

Cartier’s 1904 Santos, famously designed for aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, is often cited as the first purpose-built men’s wristwatch, and by the 1910s, brands like Girard-Perregaux were producing wristwatches en masse for German naval officers.

The Strap Gets Technical

While early watch straps were primarily leather, war once again drove innovation. The NATO strap, seen today in military watches from the likes of Bremont and and OMEGA, was developed by the British Ministry of Defence in 1973. It wasn’t luxurious, but it was nearly indestructible.

Equally, divers needed something that could survive saltwater and pressure at depths beneath the big blue. Diving wasn’t the big business it is today, and the inherent dangers that exist underwater were only more prevalent back in the day. Divers needed a timepiece that could go the difference; in an environment that we had no business being in.

Brands like Blancpain, Doxa, and even Rolex and its Submariner collection made perforated rubber design the norm through the 1960s, quickly became the de facto strap for aquatic missions for its comfort and functionality. It’s no wonder we saw the SUB300 on the wrists of intrepid explorers like Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

The Birth of Integration: Genta and the Bracelet Revolution

Up until the 1970s, the case and strap remained two distinct components, with the former quite rightly commanding the attention of the era’s avid collectors.

But along came the quartz crisis which put the Swiss legacy brands and their automatic watches on turbulent ground. So in 1972, when Gérald Genta unveiled the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, a luxury sports watch in stainless steel with an integrated bracelet that flowed directly from the case, it marked a radical shift in perspective for the horological market.

Two years later, Patek Philippe’s Nautilus (Ref. 3700/1) followed suit, cementing the integrated bracelet as a new design language; one that every collector and his dog was desperate to acquire.

Brands like IWC and Vacheron Constantin embraced the style with releases such as the Ingenieur and 222, respectivey, defining what we now call the luxury sports watch. These pieces were rugged, elegant, and wearable with everything from swim shorts to a dinner jacket.

The Rise of Modularity: Quick-Change Systems and the Modern Collector

With fewer buyers owning multiple timepieces, the ability to adapt a single watch to multiple scenarios has become a key value proposition. Brands have responded with modularity in mind, giving wearers ultimate freedom to change up their favourite timepiece’s appearance with a deft flick.

Cartier’s QuickSwitch system, found on models like the Santos de Cartier, allows wearers to swap between leather, steel, and rubber straps with the push of a button. No spring bar tools required.

Vacheron Constantin’s Overseas, launched in 2016, came standard with three strap options – leather, rubber, and steel – all interchangeable with a proprietary system. Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Polaris and IWC’s Pilot’s Watch Chronograph 41 have followed this path too.

At the microbrand and indie level, manufacturers like H. Moser & Cie., Nomos, and Christopher Ward offer tool-free strap swaps; a nod to modern lifestyles, not just watchmaking tradition.

Even Apple, arguably the most-worn wristwatch today, was leaving money on the table with the rise of knock-off brands developing cheap and accessible strap options for the tech giant’s most popular models.

Apple has since made strap-swapping a centrepiece of its product design, offering hundreds of variations across leather, silicone, textile, and metal. The Ultra even offers an Hèrmes option, for the metro man.

Straps Address a Modern Problem

From a commercial perspective, straps are big business. Brands have realised that straps drive re-engagement after the customer inevitably gets tired of seeing the same $20,000 watch on the wrist each morning. I know, it’s the worst. But a $400 strap can breathe new life into any timepice.

Hermès, F.P. Journe, and Richard Mille all sell luxury straps that serve both aesthetic and profit margins. There are even independent strap-makers that have built entire businesses around this aftermarket demand.

At times, it feels like the luxury consumer doesn’t want more watches; they want more ways to wear the ones they already love. Whether you’re suiting up for a film premiere wearing the A. Lange & Söhne Odysseus or slipping into a quiet cinema seat solo rocking a TAG Heuer Aquaracer, your watch can adapt to meet the situation. The perfect example of function and fashion, when one watch can become many.