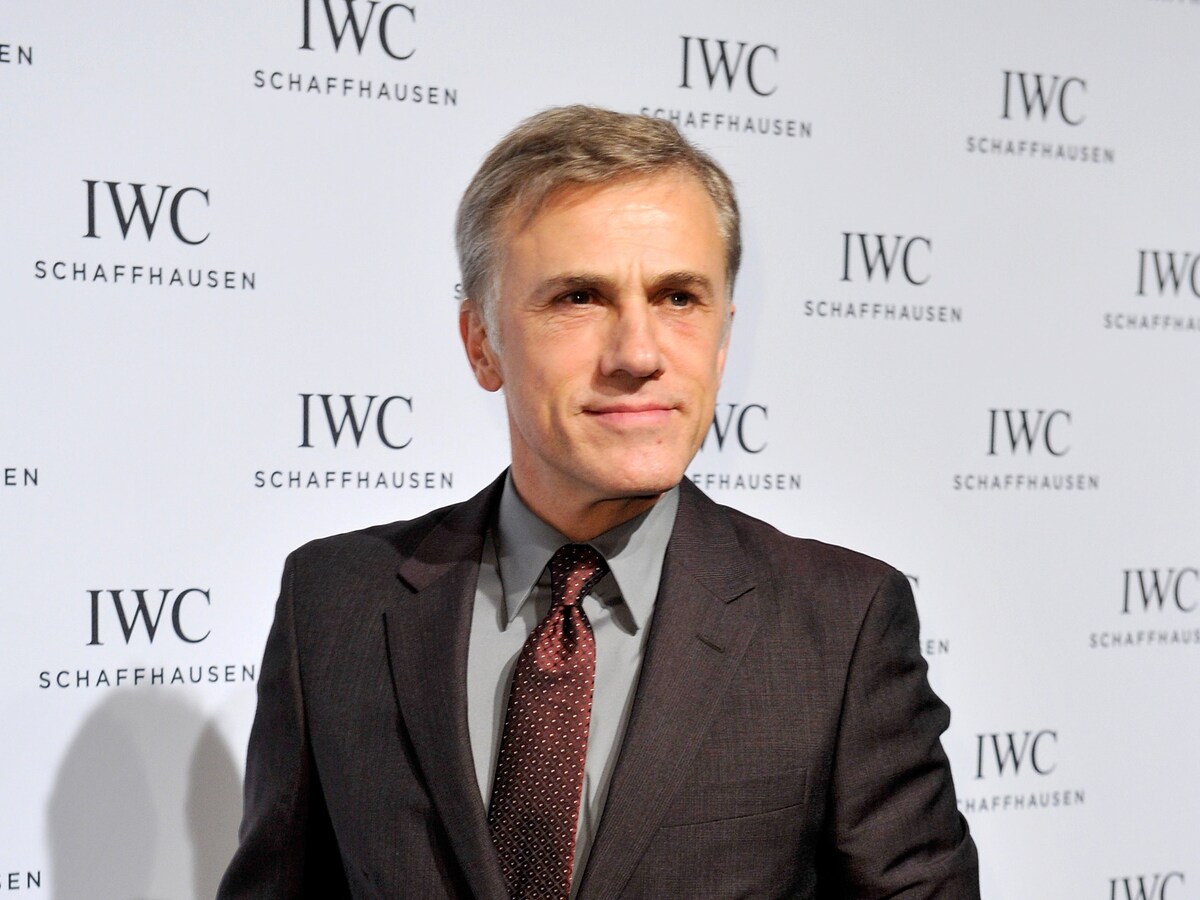

Christoph Waltz is a rare breed of gentleman in a world filled with shirtless one-hit wonders and loud social media operators. “I don’t consider ‘dude’ a compliment,” he says in his unmistakable tone, reflecting on the fall of the gentleman and the unfortunate rise of modern bravado.

Waltz has earned a reputation as Hollywood’s go-to villain. But behind the polished performances in Tarantino films and Bond blockbusters lies a man who defies cliché.

He is thoughtful, measured, and unapologetically intellectual. And even now, well into his sixties, he remains sharper than most.

Curated news for men,

delivered to your inbox.

Join the DMARGE newsletter — Be the first to receive the latest news and exclusive stories on style, travel, luxury, cars, and watches. Straight to your inbox.

At this point in his career, Waltz has little to prove. But in person, he is just as compelling as he is on screen. We sat down with him to talk about watches, personal style, growing older in the spotlight, and how to survive a career in acting without losing your soul.

“I think one of the most important qualities of style is discreteness.”

On a crisp winter morning in Geneva, having just touched down, Waltz was en route to the Mandarin Oriental. But not before carving out a moment for us.

He has spent over three decades in show business, yet it was 2009’s portrayal of Colonel Hans Landa in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds that launched him to international acclaim. The performance earned him an Oscar, a Cannes trophy, and a spot in the cultural memory bank. More recently, he portrayed the calculating Blofeld opposite Daniel Craig in Spectre.

So what did we ask him about when given the chance to sit down? None of that. This wasn’t a press junket. It was something much better.

At this year’s SIHH in Geneva, Waltz served as an ambassador for IWC. Naturally, we were curious why he chose to align with the brand. Was it a cheeky nod to his Bond villain status, given 007’s preference for a different Swiss marque?

“Because they asked me,” Waltz quipped. Turns out, even Hollywood’s smoothest villain can play for laughs.

“I’m not into watches that scream for attention. I prefer things made with care and restraint. IWC is grounded in tradition, with clear design and mechanical substance. That’s what I connect with.”

Before partnering with IWC, Waltz rarely wore a watch. It was this collaboration that brought him into the world of horology. Even now, he still views a timepiece as something to appreciate, not simply to wear out of habit.

“You don’t need a watch unless you like the watch. If I really need to know the time, I can look up at a church tower.”

This mindset runs deep. Waltz sees style as something best kept subtle. He has no need for excess and no desire to chase trends.

“I sort of regret the vanishing of the gentleman. I regret the promotion of the ‘dude’. I don’t consider ‘dude’ a compliment.”

When asked to define his approach to style, Waltz responded with typical brevity: “It wouldn’t be style if I talked about it. The rest is fashion. And I’m not into fashion.”

He doesn’t believe every man has to be a gentleman. But he does think the world would benefit if more of them tried.

So was Christoph Waltz ever a ‘dude’ in his youth?

“No. I was never a dude. I never subscribed to that mentality. Discreteness has always been essential.”

He spent his school years in a strict boarding environment. No clubs. No rebellion. No loud music. And definitely no wild phases. “I never needed to break free. I followed my interests and never abused my freedom,” he says.

His rise to global stardom came long after most actors would have called it quits. This may be why Hollywood never got to his head. Fame found him late. And he was ready.

“It gave me time to live on the other side. To understand what it means not to be famous. That helped when it finally came.”

He is the first to admit luck played a part. “I contributed for thirty-five years and nothing happened. When it did, yes, I contributed again. But it was still luck.”

“As a young person, you’ll need an unusually independent mind to avoid the ‘Dickhead Factor.’”

We asked Waltz about the modern actor’s biggest trap: instant fame turning into instant arrogance. He calls it the ‘Dickhead Factor’.

“Being young means pushing boundaries. You should do that. But know there are consequences. Acting like a dickhead isn’t the issue. The problem is when it ends, and you don’t know who you are without it.”

At the end of our interview, it becomes clear that Waltz has no desire to reinvent chivalry. He is not campaigning to save manhood. He is just being himself.

“Things change. But that doesn’t mean standards have to fall. We have more tools today. So why is the quality worse?”

Insanity may thrive in the modern world, but Waltz remains content as the calm, articulate outsider. The accidental gentleman. And perhaps, the last one standing.